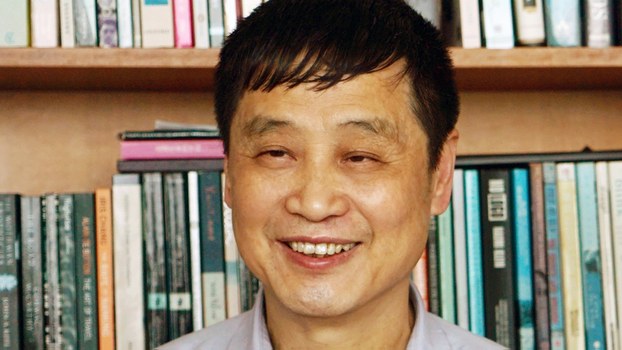

As China moves further away from the Cultural Revolution era, a few voices within the country remain determined to keep the memories alive, and one of the most prominent among them is Xu Youyu. A scholar and participant in the 1989 Tiananmen protests, Xu has spent years wrestling with China’s official narrative of the Cultural Revolution. His work is not just a quest to preserve history but a call for a political awakening that rejects the erasure of memory.

Xu Youyu’s life has been marked by a deep engagement with the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath. Born in Chengdu in 1947, Xu participated in the Red Guard faction during the Cultural Revolution. He experienced firsthand the chaos and ideological fervor that swept through China, later reflecting on those years through a liberal lens. His commitment to understanding and documenting the events surrounding the Cultural Revolution has led him to become a key advocate for the creation of a non-official history of that period.

Despite the Communist Party’s resolution in 1981, which sought to close the chapter on the Cultural Revolution by attributing 70% of Mao’s actions to positive contributions, Xu’s writings expose the gap between official accounts and the lived experiences of millions. The government’s effort to frame the Cultural Revolution as an anomaly to be condemned, without addressing the fundamental issues of totalitarianism, has led to a dangerous forgetting of history.

Xu’s writings are marked by a careful examination of memory and its role in shaping the future. He argues that without confronting the past, the same ideological forces could re-emerge, leading China back toward a totalitarian system. He believes that the most crucial step toward preventing a repetition of the Cultural Revolution is to write the history in a way that allows future generations to learn from it. This history, however, must be untainted by official ideologies or myths. It must reflect the diverse perspectives of those who lived through it, including former Red Guards, intellectuals, and those who suffered under the regime.

Xu’s analysis extends beyond the formal events of the Cultural Revolution to examine the psychology of the participants. His research, which includes interviews with former Red Guards, delves into the personal motivations behind the movement. Xu’s objective is not just to document the events but to understand the ideological manipulation that occurred during this period.

In contrast to the official narrative that portrays the Red Guards as champions of Maoist ideals, Xu insists that the movement was controlled by the Communist leadership and was not an expression of genuine popular will. The Red Guards, he argues, were manipulated by the state, driven not by a desire for democracy but by ideological conformity imposed by the Party.

As China experiences rapid economic modernization, Xu’s work serves as a cautionary tale. He warns that without a full reckoning with the Cultural Revolution, China risks repeating the mistakes of the past. He calls for the establishment of a “Museum of the Cultural Revolution,” a place where people can engage with this dark chapter of their history and come to terms with its consequences. This museum, Xu believes, would be a vital step in the ongoing effort to rebuild the social fabric and prevent history from repeating itself.

Xu’s work is not only an academic pursuit but also a political act. By advocating for the preservation of memory and the creation of spaces where this history can be debated, he challenges the current political climate in China. He seeks to foster a collective understanding that does not rely on the state’s version of events but one that allows for personal stories and the complex realities of the Cultural Revolution to emerge.

Xu Youyu’s insistence on preserving the truth of the Cultural Revolution is a vital intervention in a society where the memory of the past is tightly controlled. His work seeks not only to educate the present generation but to create a political opposition that can learn from past mistakes. In doing so, he aims to offer China a future that is free from the shadow of totalitarianism and grounded in a deeper understanding of its own history.